Building complex crossings.

How I built this…

While hunting through some images on my hard drive the other day I found a series of pictures I thought were lost. When building the trackwork for the layout I really didn’t take a lot of pictures of the actual track building process. However I distinctly recall snapping a series of shots while building one of the more complex sections, but I haven’t seen them since building this piece of track back in March of 2007

Fortunately, this series surfaced and I thought modelers might find it interesting to see the process I used to build some of the more complex pieces for the layout.

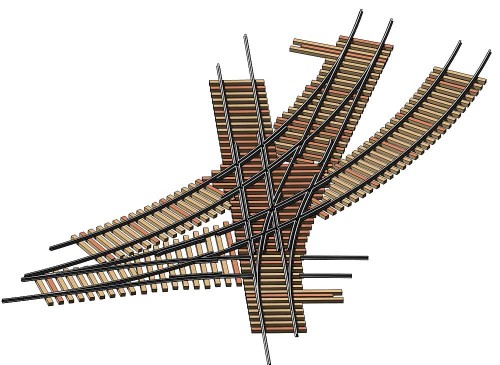

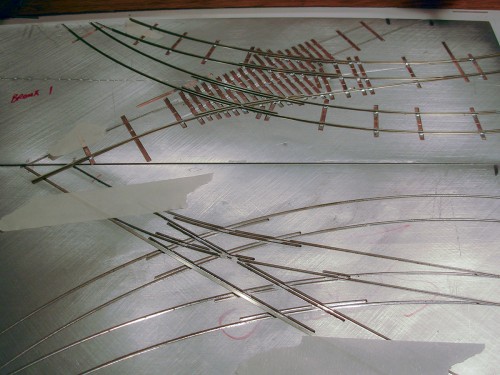

The CAD drawing for this piece of trackwork, which is the most complex on the layout. Three turnouts are overlapped sharing one common frog. Each piece of trackwork for the layout started with a precise 3D drawing that I used to get the location of each tie correct.

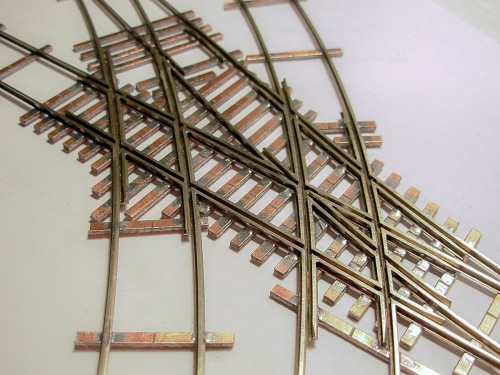

The image above is a scan from an old magazine article showing this piece of track. In the centre top of the image you can see where the three turnouts form a rather interesting frog. Surely a one of a kind.

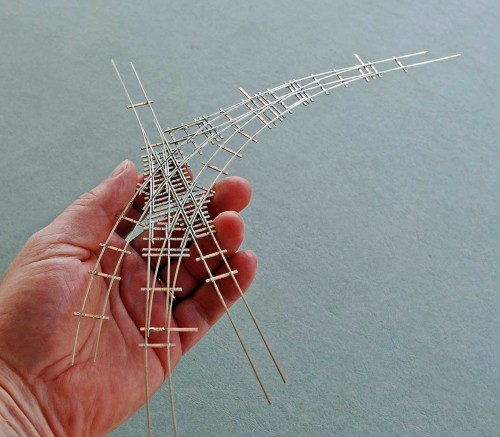

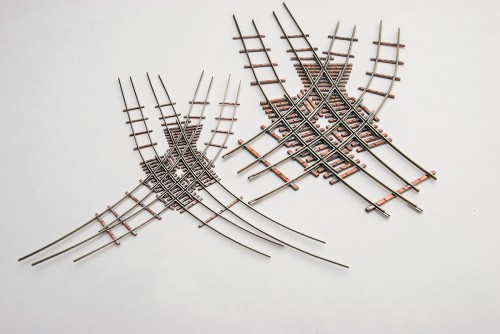

The picture above shows my HO scale version of it, rotated 90 degrees clockwise from the magazine image.

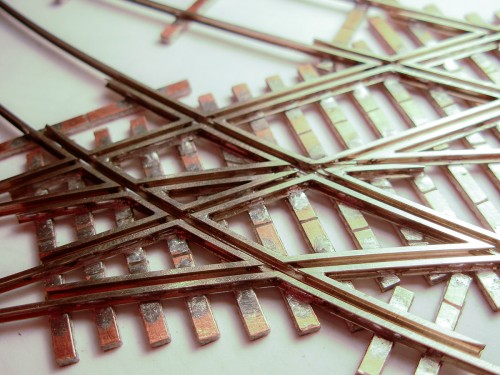

And just for shits and giggles, here it is in N scale, code 40 rail…

So how was it made?

These pieces weren’t built using the same techniques as standard turnouts. To build this piece, and the Quadruple Diamond, I had to develop a new technique and style of fixture to allow me to properly form all the pieces of rail as simply as possible.

These are the fixtures used to build the piece. If you look closely you can see that they are mirror images of each other. The fixture at the top has the tie pockets machined into it, the bottom is just the rail grooves. The top fixture is the correct layout for the trackwork and has part of the piece already built. The bottom fixture has a length of rail taped into it, upside down. The width of the groove is the same as the base of the rail, and there is clearance deep into the fixture to accommodate the top of the inverted piece of rail.

The upper fixture is for assembly, the lower fixture is a grinding jig.

To build this piece as simply as possible, it is made from as few pieces of rail as possible. The entire finished piece of trackwork consists of only 8 stock rails and 8 guard rails. The rails are simply notched to form a lap joint between the two rails that cross each other. The lap is ground in one rail from the top down, halfway, and in the other from the bottom up, again half way. This allows the two rails to be placed into the assembly fixture as solid lengths and soldered in place. The alternative to this method would be to form dozens of fiddly pieces of rail accurately, ain’t nobody got time for that.

Enough blather, lets see some pictures

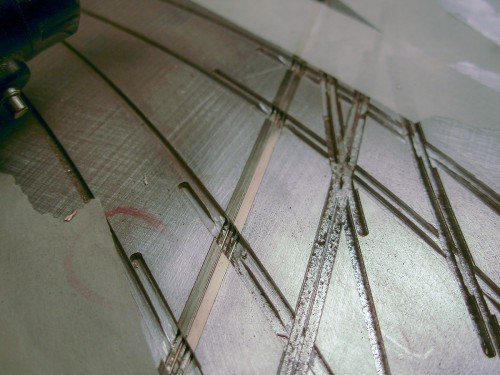

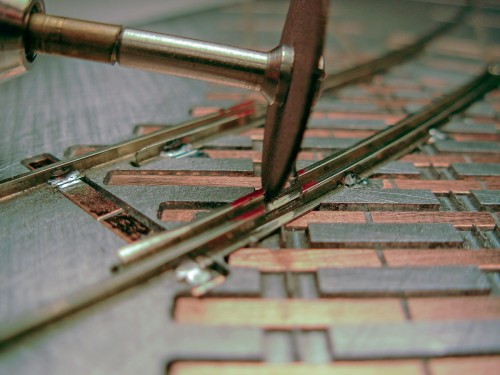

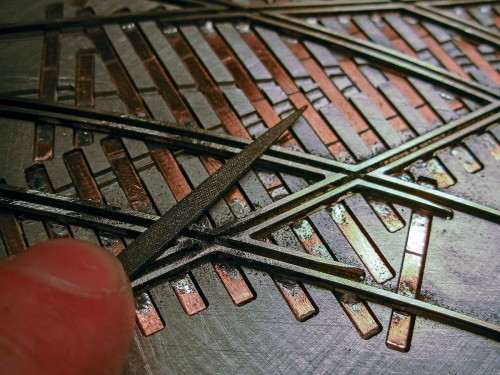

In this picture I have placed both the stock and guard rail lengths into the inverted version of the fixture and held them in place with tape. The bottom of the rail is facing up and is just flush with the surface of the fixture. Using a Moto-Tool with a thin ceramic disk I very carefully grind down through half the thickness of the rail. The rail grooves in the fixture provide a precise guide for where to grind.

Clicking on the image for the large version you can see how this was done.

Notches in both rails complete.

Here is the finished piece of rail with the grooves in the base. I ground from the bottom up just past the middle of the web of the rail, leaving the head of the rail intact.

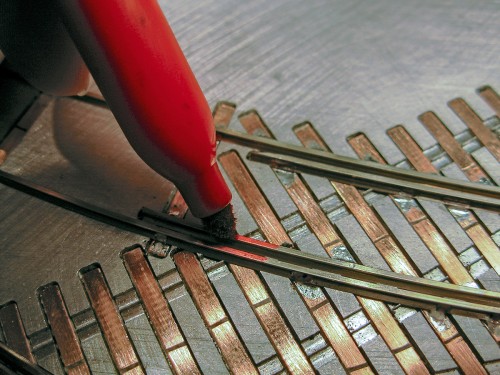

Next, on the rail(s) in the other fixture that the rails I just ground have to cross, I mark the head of the rail with ink.

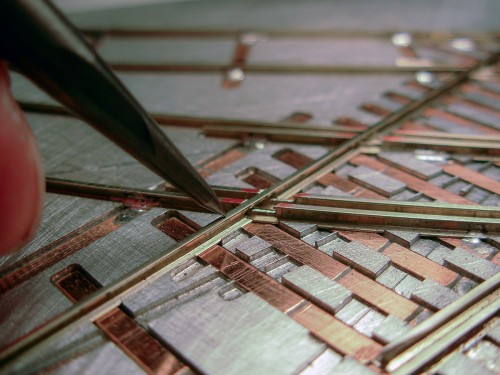

The rail with the base ground is then layed over top of the rail it will cross. The rail is held into the fixture with tape (not shown in this image). With the rail in place, a sharp scriber is used to mark the top of the rail where this rail will cross. The rail at this point won’t sit down into the fixture until the top of the other piece is ground, but it is close enough to add the scribe lines.

Using those marks as a guide, the rail is ground from the head down to the middle. This takes a very steady hand and lots of light to see clearly. This is one of the rare instances where I actually wore safety glasses, those ceramic wheels explode quite nicely…

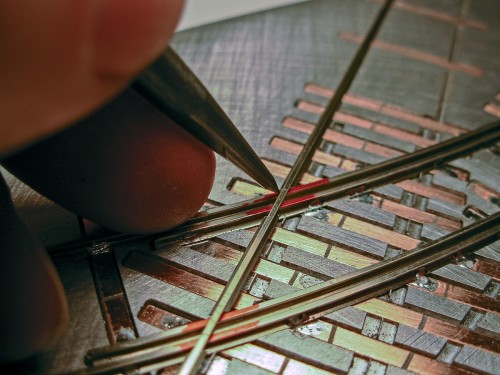

Here, the gaps have been ground into the rails of the trackwork. Clearance is now there for the opposing route to cross.

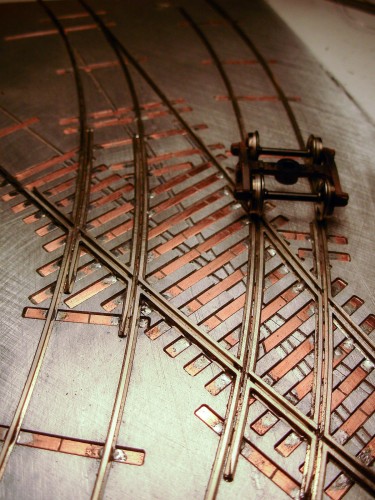

The rail ground in the inverted fixture is now placed on top of the rail in the normal fixture. It is precisely ground and crosses the route perfectly. This process will be repeated for the adjacent guard rail.

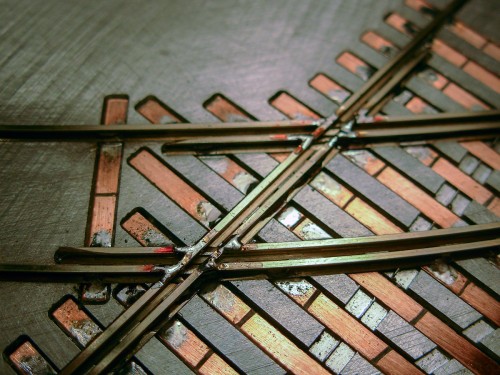

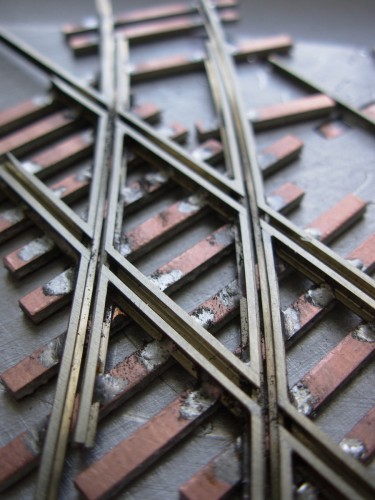

Here are all the pieces in place, ready to solder. Damn, that looks good, I forgot how much I enjoyed this process. Looking at a large version of the picture, I can see that the guard rail has the bevel on the leading edge ground on the wrong side! Don’t tell anyone…

With everything in place, the rails are soldered to the PC board ties as well as each other. I sweated solder down between the joints, but don’t fill the flangeways with it, which makes it difficult to clean up.

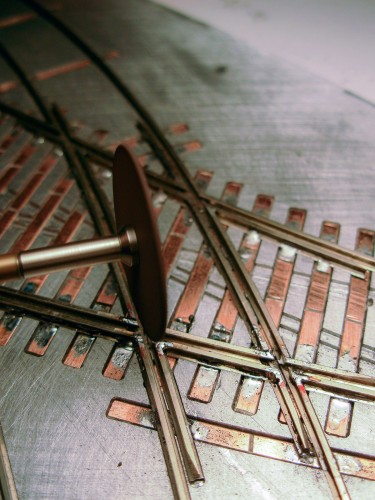

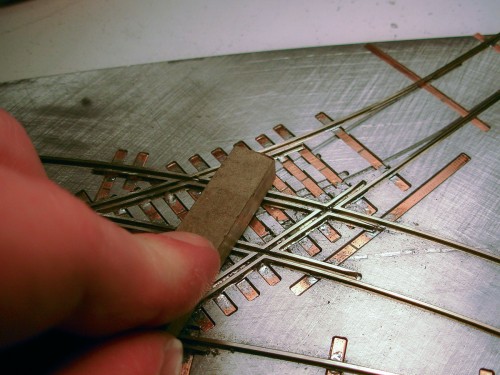

Back to the trusty ceramic cut off wheel in the Moto-Tool. The flangeways are very carefully cleaned out. The web of the lower rails will be in the flangeways and need to be removed. This takes a very steady hand as any mistake here can not be repaired. I just get it close, and clean it up with hand files later.

Using a flat file, the top of the rails are all cleaned of solder. It looks like a real mess, but it will clean up nicely. This step is where the geometry really starts to reveal itself.

I carefully clean up the inside edge of the running rails with needle files, shaping the frog points precisely.

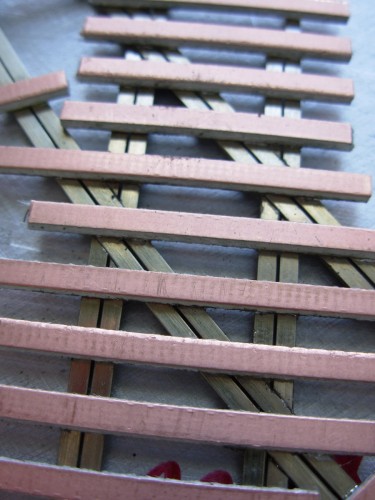

I used a series of progressively finer grades of sandpaper fixed to hardwood blocks to smooth out the top of the rail, removing all the scratches left from the filing process. During this step any flaws will be revealed and can be fixed. The dark dirt left behind from the sanding process really helps to see the geometry of the trackwork.

Here are the finished rails in place, carefully filed and polished. The resulting trackwork runs flawlessly.

From the bottom the precise grinding can be seen on this crossing.

This is the same process used to make the N scale code 40 version. Building those pieces took some exceptional care when grinding that tiny rail!

The HO and N scale version of the Quadruple Diamond from the centre of the terminal. Both these pieces were built from 8 pieces of rail simply overlapped to form that complex curved geometry.

About the Author:

I'm your host, Tim Warris, a product developer in Port Dover, Ontario. Since March of 2007 I have been documenting the construction of the former CNJ Bronx Terminal in HO scale. For my day job, I design track building tools for Fast Tracks, a small company I own and operate. Fast Tracks makes it fast and easy to hand lay your own trackwork. Stop by our website to learn more!

Posted by: Tim | 06-21-2013 | 03:06 PM

Posted in: Latest Posts | Track Construction

Tres complexe mais tellement beau comme réalisation ‘chapeau’ comme on dit chez nous.

A+ amicalement

Philippe

And to think, I a mere mortal, have been thinking how cool it would be to do this for my own layout when now I find out you used your own special sneaky way of doing it! 🙂 It’s pretty cool actually! Would you ever rent those jigs? Keep up the good work and super cool projects.

OK, I’m impressed! (I use the Fastracks jigs, and have built “one off’s” by hand – no jig) I want to build a curved crossing at an odd angle (about 80 deg.) I now know how to do it! BTW: what about the gaps and powering the crossing?

I will not be tackling anything quite so challenging myself, but I do like to see what can be done.

Uhm.. besides the wide amount of questions this impressive work could set in my mind, the most extraordinary thing to me is: how did you manage to avoid massive shortcircuiting in this track work?