National Train Show – Cleveland, Ohio. July 18-20, 2014

Just a couple weeks to go and for the first time in over a year the CNJ Bronx Terminal will be set up an operating in the Fast Tracks booth at the NMRA Train Show in Cleveland, OH.

As the layout is currently in storage, I don’t have any opportunity to work on it, which would explain the lack of progress…. Fortunately, with the acquisition of newer larger facilities for Fast Tracks (I own Fast Tracks), there will finally be permanent display and working space available for the layout! We expect to be in the new facilities this fall.

Needless to say I am certainly looking forward to finally being able to get back to work on it!

The new location, a second story loft in a former factory is the perfect setting for the layout! Ample space will be devoted to the setup so people visiting can finally get a chance to see the layout up and running. Room for a workbench will also be provided so layout can soon be finished!

How I built this…

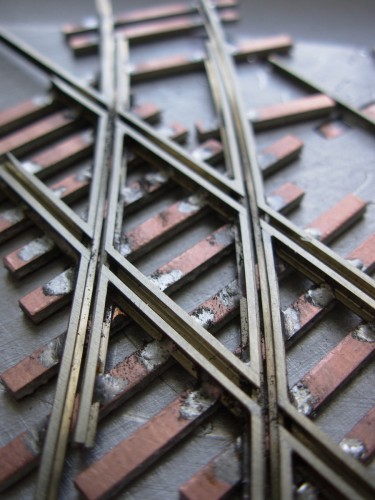

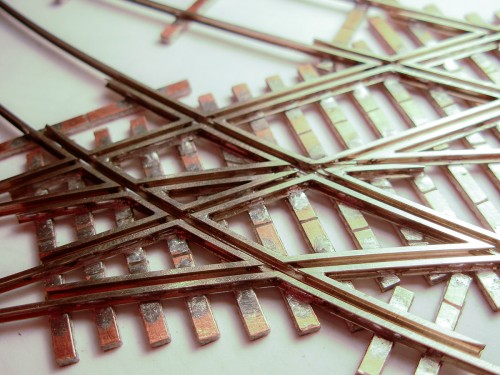

While hunting through some images on my hard drive the other day I found a series of pictures I thought were lost. When building the trackwork for the layout I really didn’t take a lot of pictures of the actual track building process. However I distinctly recall snapping a series of shots while building one of the more complex sections, but I haven’t seen them since building this piece of track back in March of 2007

Fortunately, this series surfaced and I thought modelers might find it interesting to see the process I used to build some of the more complex pieces for the layout.

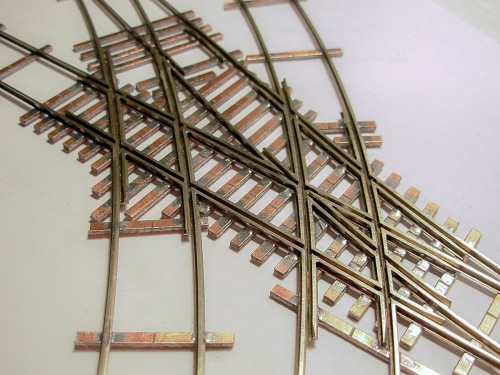

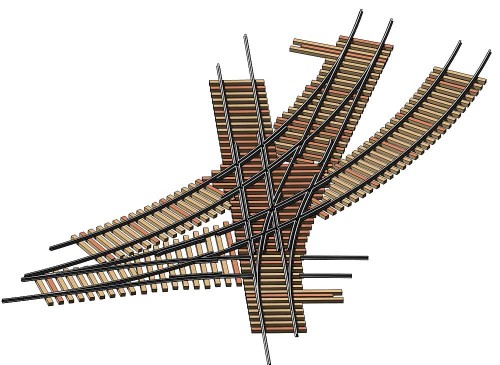

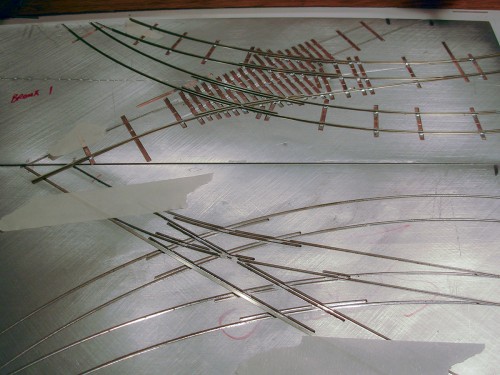

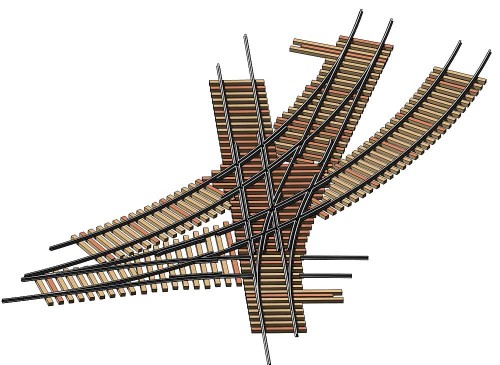

The CAD drawing for this piece of trackwork, which is the most complex on the layout. Three turnouts are overlapped sharing one common frog. Each piece of trackwork for the layout started with a precise 3D drawing that I used to get the location of each tie correct.

The image above is a scan from an old magazine article showing this piece of track. In the centre top of the image you can see where the three turnouts form a rather interesting frog. Surely a one of a kind.

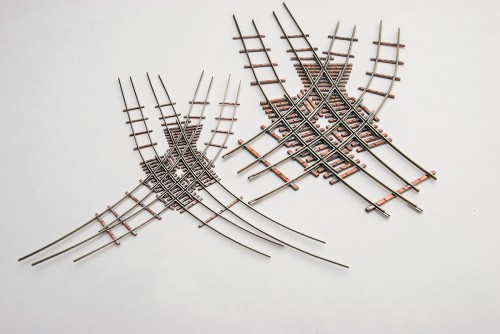

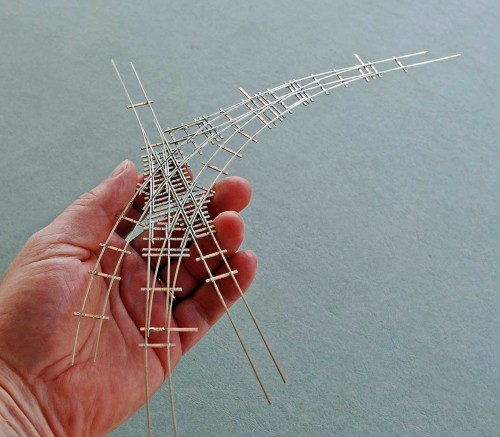

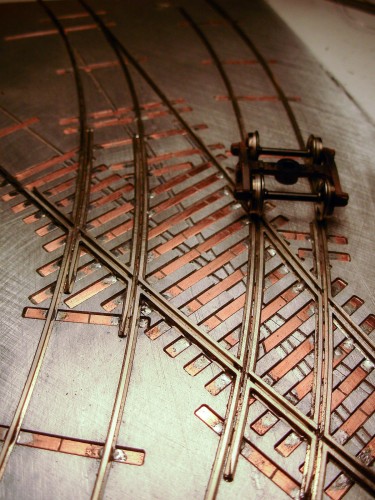

The picture above shows my HO scale version of it, rotated 90 degrees clockwise from the magazine image.

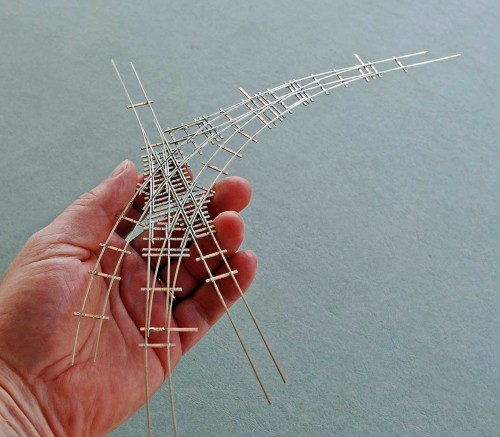

And just for shits and giggles, here it is in N scale, code 40 rail…

So how was it made?

These pieces weren’t built using the same techniques as standard turnouts. To build this piece, and the Quadruple Diamond, I had to develop a new technique and style of fixture to allow me to properly form all the pieces of rail as simply as possible.

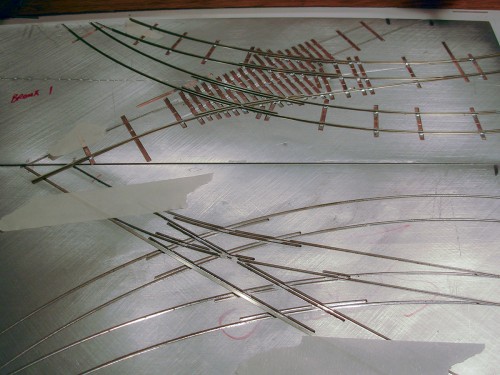

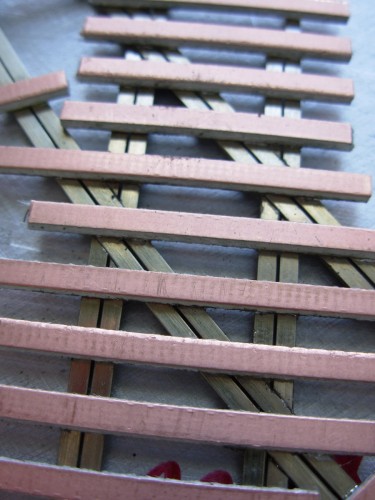

These are the fixtures used to build the piece. If you look closely you can see that they are mirror images of each other. The fixture at the top has the tie pockets machined into it, the bottom is just the rail grooves. The top fixture is the correct layout for the trackwork and has part of the piece already built. The bottom fixture has a length of rail taped into it, upside down. The width of the groove is the same as the base of the rail, and there is clearance deep into the fixture to accommodate the top of the inverted piece of rail.

The upper fixture is for assembly, the lower fixture is a grinding jig.

To build this piece as simply as possible, it is made from as few pieces of rail as possible. The entire finished piece of trackwork consists of only 8 stock rails and 8 guard rails. The rails are simply notched to form a lap joint between the two rails that cross each other. The lap is ground in one rail from the top down, halfway, and in the other from the bottom up, again half way. This allows the two rails to be placed into the assembly fixture as solid lengths and soldered in place. The alternative to this method would be to form dozens of fiddly pieces of rail accurately, ain’t nobody got time for that.

Enough blather, lets see some pictures

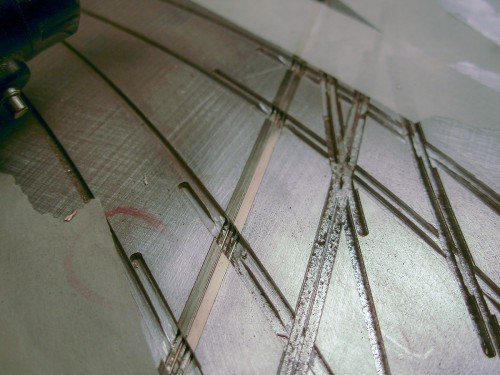

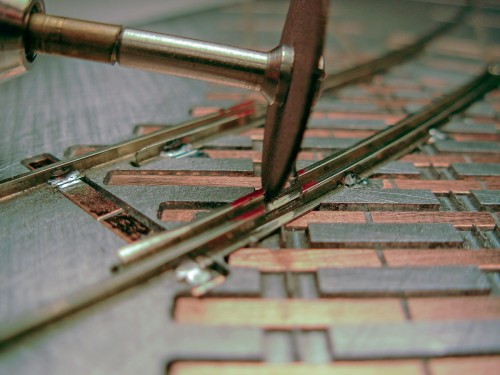

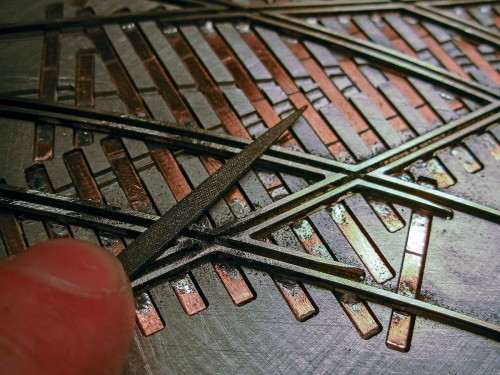

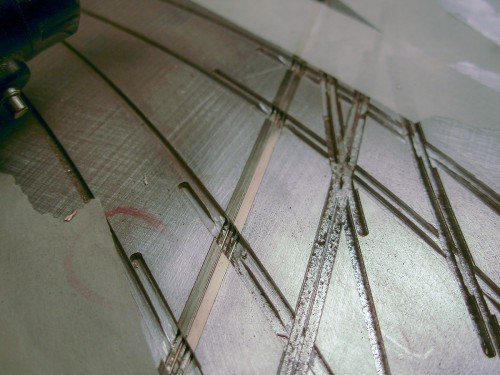

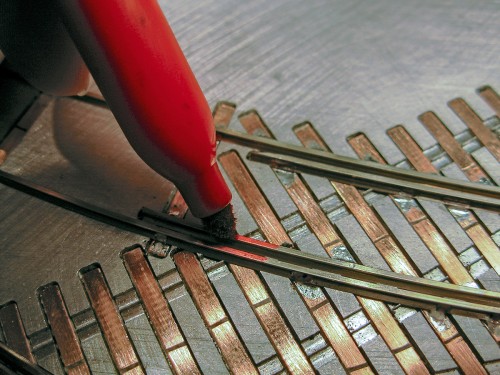

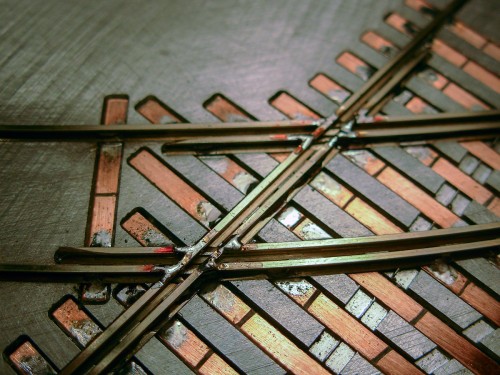

In this picture I have placed both the stock and guard rail lengths into the inverted version of the fixture and held them in place with tape. The bottom of the rail is facing up and is just flush with the surface of the fixture. Using a Moto-Tool with a thin ceramic disk I very carefully grind down through half the thickness of the rail. The rail grooves in the fixture provide a precise guide for where to grind.

Clicking on the image for the large version you can see how this was done.

Notches in both rails complete.

Here is the finished piece of rail with the grooves in the base. I ground from the bottom up just past the middle of the web of the rail, leaving the head of the rail intact.

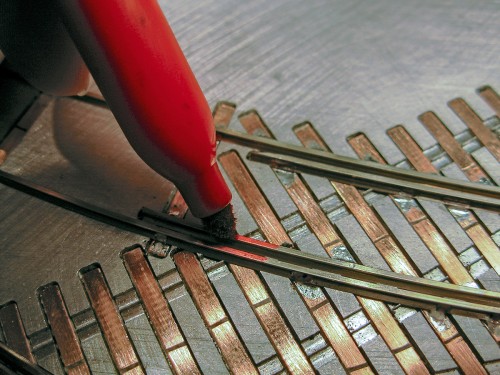

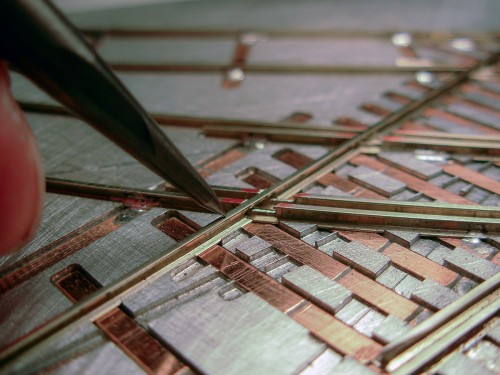

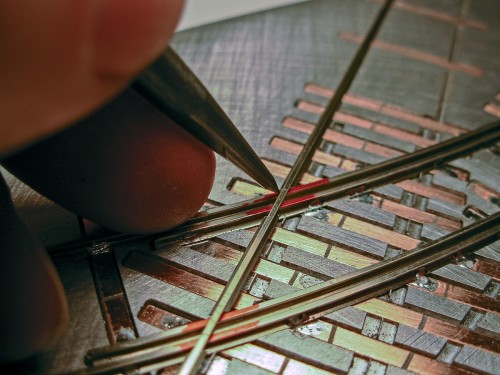

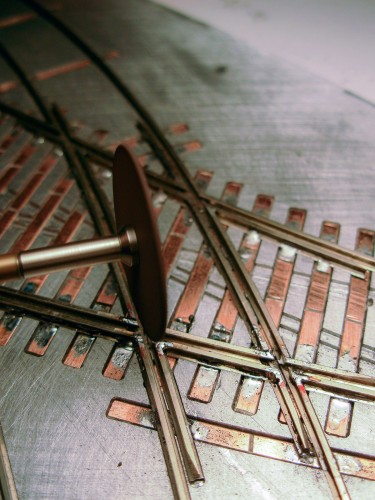

Next, on the rail(s) in the other fixture that the rails I just ground have to cross, I mark the head of the rail with ink.

The rail with the base ground is then layed over top of the rail it will cross. The rail is held into the fixture with tape (not shown in this image). With the rail in place, a sharp scriber is used to mark the top of the rail where this rail will cross. The rail at this point won’t sit down into the fixture until the top of the other piece is ground, but it is close enough to add the scribe lines.

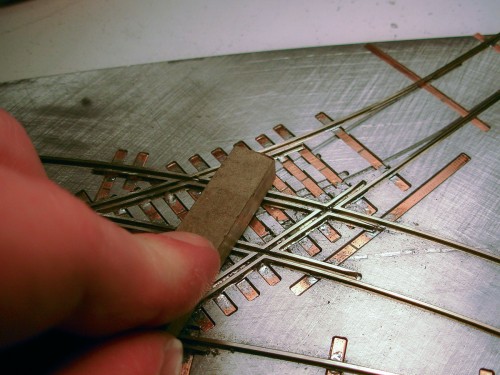

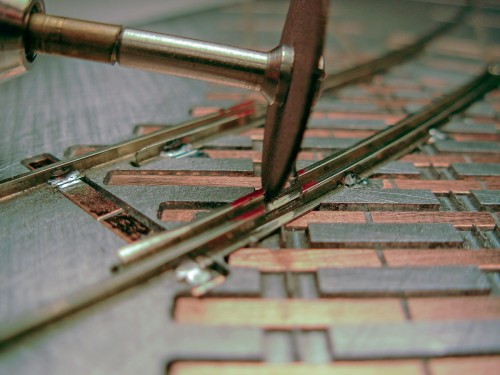

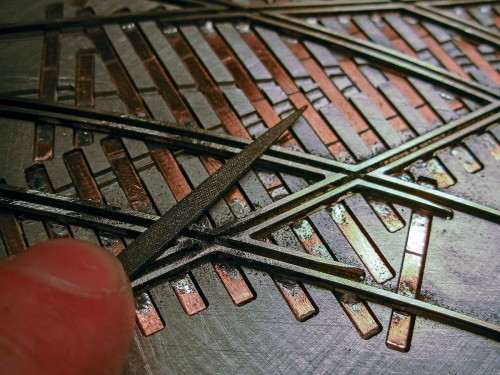

Using those marks as a guide, the rail is ground from the head down to the middle. This takes a very steady hand and lots of light to see clearly. This is one of the rare instances where I actually wore safety glasses, those ceramic wheels explode quite nicely…

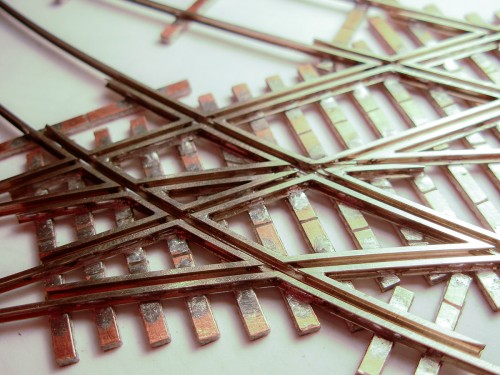

Here, the gaps have been ground into the rails of the trackwork. Clearance is now there for the opposing route to cross.

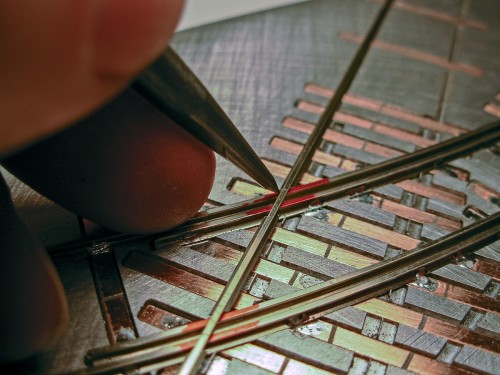

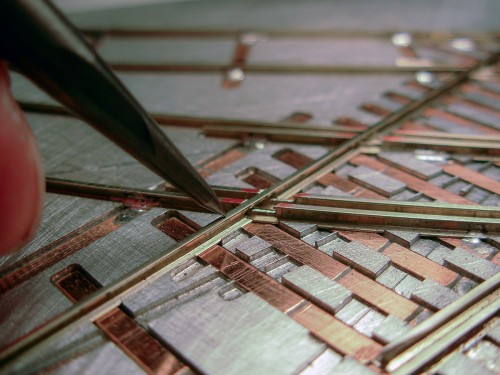

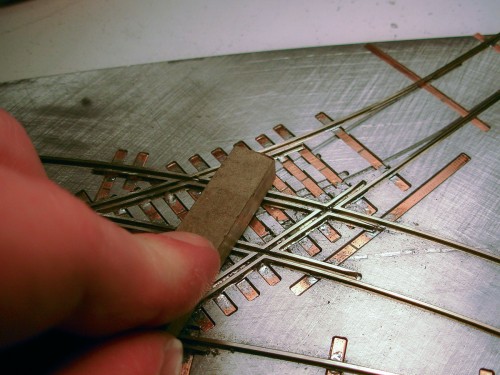

The rail ground in the inverted fixture is now placed on top of the rail in the normal fixture. It is precisely ground and crosses the route perfectly. This process will be repeated for the adjacent guard rail.

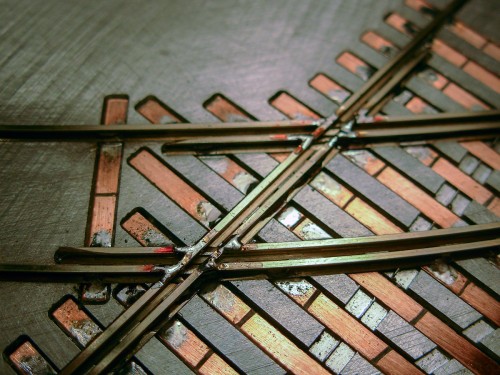

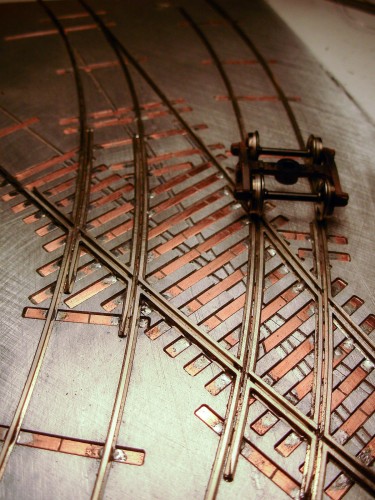

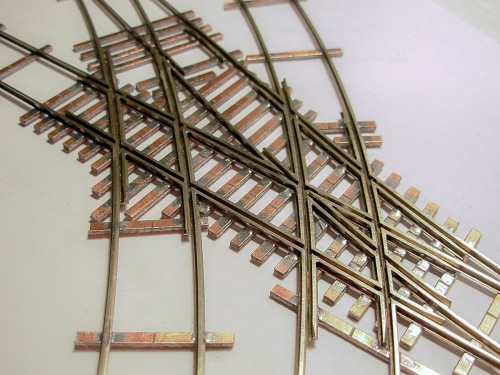

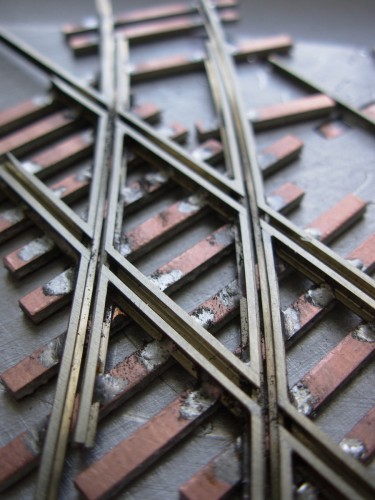

Here are all the pieces in place, ready to solder. Damn, that looks good, I forgot how much I enjoyed this process. Looking at a large version of the picture, I can see that the guard rail has the bevel on the leading edge ground on the wrong side! Don’t tell anyone…

With everything in place, the rails are soldered to the PC board ties as well as each other. I sweated solder down between the joints, but don’t fill the flangeways with it, which makes it difficult to clean up.

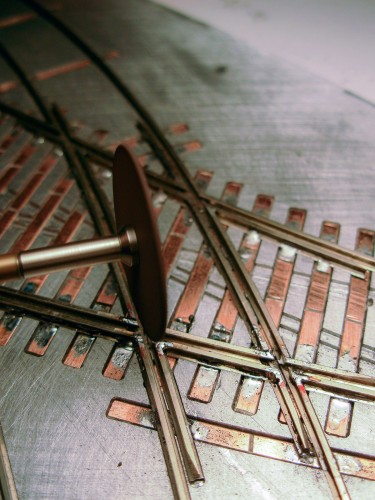

Back to the trusty ceramic cut off wheel in the Moto-Tool. The flangeways are very carefully cleaned out. The web of the lower rails will be in the flangeways and need to be removed. This takes a very steady hand as any mistake here can not be repaired. I just get it close, and clean it up with hand files later.

Using a flat file, the top of the rails are all cleaned of solder. It looks like a real mess, but it will clean up nicely. This step is where the geometry really starts to reveal itself.

I carefully clean up the inside edge of the running rails with needle files, shaping the frog points precisely.

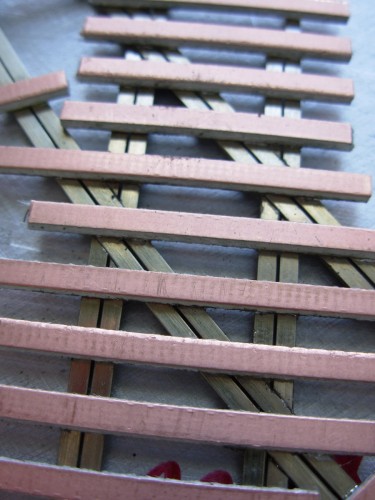

I used a series of progressively finer grades of sandpaper fixed to hardwood blocks to smooth out the top of the rail, removing all the scratches left from the filing process. During this step any flaws will be revealed and can be fixed. The dark dirt left behind from the sanding process really helps to see the geometry of the trackwork.

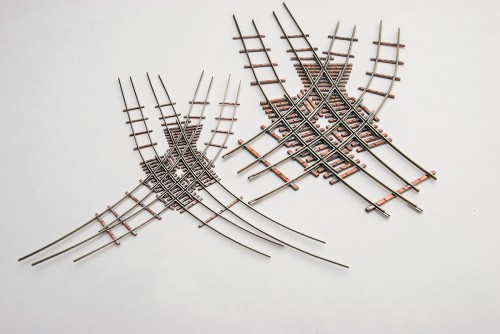

Here are the finished rails in place, carefully filed and polished. The resulting trackwork runs flawlessly.

From the bottom the precise grinding can be seen on this crossing.

This is the same process used to make the N scale code 40 version. Building those pieces took some exceptional care when grinding that tiny rail!

The HO and N scale version of the Quadruple Diamond from the centre of the terminal. Both these pieces were built from 8 pieces of rail simply overlapped to form that complex curved geometry.

That geometrical nightmare….

Next up in the construction of the layout is a project I have been putting off for some time, the “round” freight house. Not really round, its a 29 side nightmare.

Some time back, I designed and built a completely accurate mock up of what will become a detailed model of the freight house. I did this so when the layout is on display people could envision what sat inside the concentric ovals of the layout. I also did it to use when building the final model so I could trial and error out the design to be certain it would fit in place and clear the rolling stock. Which was no small challenge.

When I made up the initial CAD work for the trackwork, way back in 1999 I was just learning to use CAD systems. Unaware at the time, I made a bit of an error in the design. The straight portions of oval loops around the freight house were not parallel, they are off by about 2.5 degrees. I used that original CAD work done years earlier to make the test fixtures when I started playing with the idea of building the layout. I didn’t know then there was an issue in the design, and made all the fixtures and trackwork from that original flawed design.

2.5 degrees is not noticeable and the final trackwork looks and functions great.

Then I tried to build the freighthouse…

In 1907, “The Railroad Gazette” published plans and drawings on this nifty terminal recently built in The Bronx. I was able to get a copy of this article and used it in the design on the first attempt at building the freight house.

Since I was exuberantly confident that my CAD work was infallible, I dove right in and spent a few weekends building the freight house mock up. Once done I attempted to put it in place only to discover just how much 2.5 degrees really is.

There was no way it would fit. It was too big at one end and too small at the other. The straight sections were noticeably inaccurate and there was no way a string of freight cars could navigate their way around the building without hitting it. After an appropriate amount of swearing, I went back to the drawing board.

There were two possible options. One, redesign and build all the trackwork again, or “fudge” the freight house design a bit. Since it took a couple of years to design, build, install and wire up all that trackwork, I opted for the latter…

I made a 3D SolidWorks CAD model of the freight house in 2009 and by that time I had a bit more skill with CAD work (about 10 solid years full time of it…) This model was a “parametric” version of the freight house, which simply means that instead of drawing a wall and adding a dimension to it that show the size of the wall, I made a model of the building with dimensions that drive the size of the walls. Simply changing the dimension would change the CAD model and update all the other relationships in the model. This would allow me to tweak each section of the 29 sided nightmare as necessary to get it to precisely fit inside my oddly shaped oval. To the naked eye, it is undetectable, but mathematically each section of the building is slightly different. Using the Fast Tracks laser cutter, I cut out all the sections and built the model, which fit perfectly (the third or fourth time).

This is a computer generated rendering of the freight house mock up. Hard to see, but most of those sections are unique sizes.

The freight house mock up in place on the layout at a train show. It served me well for quite a few years, but its finally time to get the real model built!

Building the Foundation

Using styrene for the model…

This model will be built from styrene, using traditional modelling techniques.

That statement might be a bit of a surprise from those who have been following the CNJ Bronx Terminal project from the beginning. I tend to use a lot of technology in my modeling, mainly because I have easy access to it. The entire layout was designed using a parametric CAD system, a complete model of the layout exists digitally. The road bed was cut using Fast Tracks laser cutter. All the benchwork was cut on a CNC router using files extracted from that parametric 3D CAD work. The engine house was designed in 3D, and completely cut out on the laser cutter. All the PC board ties were produced on a CNC milling machine. The trackwork was built in custom designed Fast Tracks fixtures. The involvement of technology in this project is extensive.

The mock up of the freight house was also cut out on the laser.

All along I had intended on designing a detailed model in 3D of the freight house and using the laser to produce all the parts for it. And this intention delayed the project for years. One needs to remember that my day job, at Fast Tracks, involves about 90% of my time being spent in front of a pair of flat screen monitors doing CAD or design work of some sort. All day, every day, for the last 10 years.

Every time I turned to the freight house project, the first step was to do more CAD or design work, and I just don’t have it in me. After a long day, or week, of CAD work, the prospect of doing more just didn’t seem that appealing. So the project would get set aside until the next time I thought I would do some work on it, usually with the same result.

To get around this issue, I decided to toss the technology for the most part, and build the model by hand. The amount of time and effort will be about the same, but what I will be spending my time on will be more enjoyable for me. People tend to gush over the technology available to modelers such as laser cutters or 3D printers, overlooking the fact that they don’t really do anything. One must spend a lot of tedious effort to produce the necessary CAD files for these. And those files need to be extremely precise, otherwise all that nifty technology will let you down when you go to put something together. Instead of spending 10% of your time in research and design with 90% modeling, you spend 90% of the time on design and the rest modeling. These nifty machines are not the panacea they appear to be, much to the disappointment of the cheering masses of modelers out there who can’t wait for them to become cheap enough for everyone to own. But I digress….

Using the laser cut mock up I had made a few years back as a template, the foundation was framed up using styrene sheet stock and dimensional strips from Evergreen.

If you look close, you might be able to spot the subtle differences between the sections of the building to get it to fit in between the oddly shaped oval trackwork. The most visible are the small straight sections of the oval, instead of being rectangular, they are more of a trapezoid. This shape allows one end of the structure to be slightly larger than the other.

The mock up was built in five sections, so I can easily take it apart to transport. This model is quite large, about 26″ across, so a single piece would be quite unruly to move around. Remember, this entire layout is portable, designed to be fit inside a mini-van to take to shows.

The sections can be seen on the bottom view of the foundation. Simple joiners are used to connect them together, similar to how the sections of the layout work, except those are aluminum.

The mock up of the freight house sitting on the foundation. It is exactly the same size.

The office and one section of the freight house sitting on the foundation.

There is a consistent space between the track and the edge of the foundation. Getting this right with the final model is easy since the mock up was built to confirm everything would function correctly before the final model build. Getting the mock up right was no small feat!

Testing with some cars. This is a 36′ boxcar and flat car, but it works fine with 40′ as well. Even a 50′ will make its way around the structure without interference, but just barely. Just like the prototype did!

Close up detail of the simple styrene joiners to keep the foundation aligned and flat.

With the foundation complete, next up, walls!

Hopefully I can do Larry Fishers version of the freight house justice!